Blurring Boundaries Through Bharatanatyam

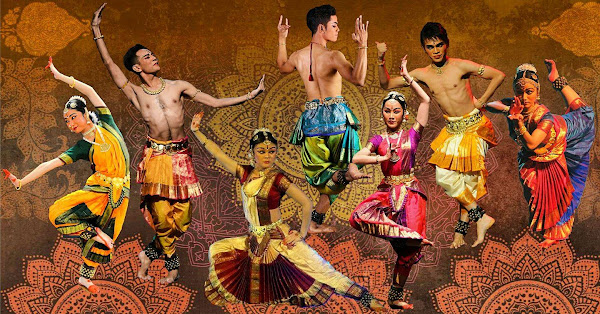

This edited article shares the journey of Malaysian dancers not of Indian ethnicity or Hindu faith who completed their Arangetram which is a solo debut performance that announces the presentation of the trained Bharatanatyam dancer on stage to the public. In Malaysia, dance is often viewed as the performative symbol of ethnic identity, and national unity, or as a tourist attraction. This is showcased at all government-sponsored platforms including global summits, sports spectacles, and state banquets. Against this social and cultural landscape in Malaysia, this article focuses on and highlights how the practice of Bharatanatyam by non-Indian, non-Hindu dancers trained at ASWARA, blurs boundaries of race and religion in embodied ways. Norbaizura Abd Ghani, Mohd Yunus Ismail, Mohammad Khairi Mokthar, Imran Syafiq Mohd Affandi, and Fatin Nadhirah Rahmat who are Malay Muslims; four Chinese namely Elaine Ng Xinying, a Roman Catholic, Kimberly Yap Choy Hoong, a Protestant Christian, Madeline Gan and Christine Chew Sie Theng, who are Buddhist, trained in Bharatanatyam for six years, and subsequently presented their Arangetram performances between 2011 and 2023.

sowing the seeds

The early Bharathanatyam dance artists in Malaysia were Indian immigrants and included two luminaries, V.K. Sivadas and Gopal Shetty who taught the Indian diaspora extensively. In 1981, together with their spiritual leader Swami Shantanand Saraswati, a monk from India, they founded the Temple of Fine Arts (TFA), a private institution for part-time students that continues to carry this torch and thrive within the Malaysian arts ecosystem today. Alternative artistic narratives and representations within Bharatanatyam in Malaysia emerged with Malay Muslim dancers, Zamin Haroon also known as Chandrabhanu in the late 1970s, and Ramli Ibrahim who danced briefly with the stage name Ramachandra, in the early 80s. Haroon made Australia his base. Meanwhile, Ibrahim elected to continue his work in Malaysia and cemented his position as artist par excellence of Bharatanatyam and Odissi, with the highest honors from the Malaysian and Indian governments, and private sectors. He established Sutra Dance Theatre in 1983.

Bharatanatyam In ASWARA

Under my dance leadership at ASWARA, the curriculum was consolidated to include intense training in genres that would reflect Malaysia’s cultural and ethnic diversity. Propelled by the philosophy of diversity, equity, Chinese dances, as well as the dances of the multiple ethnicities of Sabah and Sarawak, were added to the traditional dance modules. The Malay dance module was improved to include specific dances such as Joget Gamelan, Terinai, and Tari Inai, that were near extinction. Since 2005, the Final Graduation Exercises (PeTA) have reflected these changes. For its Bharatanatyam module, TFA was entrusted to deliver the course content. The students were drawn to and challenged by the fast and furious physicality, as well as the abhinaya which uses the face, hands, and the body to express a range of emotions. The pushpanjali, allarippu, and jathiswaram are taught in the Diploma curriculum at ASWARA. These are nritta items that comprise footwork, movements of the limbs, neck, and head as well as intricate rhythms. The remaining items that entailed more intricate coordination executed with complex rhythmic patterns, speed, stamina, storytelling, and dexterity, constitute the syllabus for Bharatanatyam majors of the Bachelor of Dance program which began in January 2008.

IMMERSION for the Arangetram

Young

Bharatanatyam exponents not of Indian

ethnicity thus began to emerge on Malaysian stages through this tertiary public

dance education system which was far removed from the private guru and studio

systems. Prior to this, Sutra Dance Theatre trained January Low and Divya Nair of

mixed-Indian parentage, as well as Michelle Chang (all now independent artists)

and Tan Mei Mei who are ethnic Chinese in Bharatanatyam and Odissi. Meanwhile,

J.T. Choong, of Chinese ethnicity, completed his Arangetram at TFA in

1994, and has worked there since as a teacher, choreographer, and performer.

The Arangetram is usually a solo evening of dance but due to rising costs, teachers have become more adaptable. The Arangetram of Abd Ghani and Ismail was presented as a duet as was Mohd Affandi and Yap’s, each lasting three hours, while the others were two-hour solos. The intense training involved the learning of new items by Kandasamy who used this opportunity to extend his creativity, capitalizing on the numerous dance languages of the ASWARA students. He incorporated movement vocabulary not always identified with Bharatanatyam including asymmetry, expansive use of space, off-balance turns, and fluid manipulation of the torso. The dancers viewed their Arangetram performance as a tremendous achievement in their lives and careers. As professionals, they recognized this as the beginning of their journeys. Mohd Affandi states that “this enabled me to grow as an artist and further equipped me with the skills to conduct Bharatanatyam classes as a certified teacher.” While the students experienced the physical and artistic transformation from the Arangetram training process, of greater relevance are the socio-cultural shifts that occurred because of their embodiment of Bharatanatyam.

NEGOTIATIONS FOR THE ARANGETRAM

Students

were introduced to new practices. Classes began and ended with the salutation

to Mother Earth, the tattikumidal,

and the closing greetings included touching or bowing at the teacher’s feet. The

Muslim dancers often found the traditions conflicting. However, due to their inherent

respect for elders as well as discussions with other teachers about

meaning and intention, they arrived at happy compromises. During training and

performance, all dancers attest to being completely immersed in their

characters and in the requirements of the art form. It is the mind and body in

unison with the music and the narrative, presenting and performing what was

poured into them through hours of rigorous practice.

For these non-Indian and non-Hindu dancers, their performance and embodiment on stage did not conflict with, or radically impact how they choose to live offstage. Rather, it generated newer understandings of other cultures, religions, and ways of being in the world. As Mokthar reflects “I do not see a “self and other”. I see myself as a performer who is a devout Muslim and loves Bharatanatyam, who embraces Malaysia’s multicultural heritage, and who has a great love for guru and the art form. I am an actor who tries to understand all the characters who may even be Gods in Hindu beliefs. It is my role as an artist to bring these narratives to the public to the best of my ability. The dancers who underwent the process of the Arangetram had to prepare to be questioned. As Mohd Affandi notes “I had to convince my father that learning Bharatanatyam had nothing to do with my faith as a Muslim. It is a beautiful dance form to express my emotions and fulfill my potential as a performer.” It was a huge hurdle that these Muslim dancers had to overcome.

MOVING FORWARD

Another area for improvement in locating this experience is that many dancers who present their Arangetram are hardly seen on stage after that. A professional collective, ASK Dance Company was established in 2011 of which the case study dancers mentioned were members at some point. The objectives of this private, full-time company were to provide an avenue for trained dancers to create further opportunities for collaboration and enhance their diverse abilities. The company stages two productions frequently - a triple-bill entitled 3 Faces that incorporates a thirty-minute segment of Bharatanatyam and Crossing Borders in Bharatanatyam, a full-length in the style of a Margam. In 2017, Crossing Borders in Bharatanatyam presented seven dancers who completed their Arangetram in one production, at the National Theatre. Mohammad Khairi Mokthar and Mohd Yunus Ismail danced for Shobana Jeyasingh productions in the UK, while Azmie Zanal Abdden who trained in Bharatanatyam but did not complete his Arangetram performed with Mohammad Khairi Mokthar and others in Mavin Khoo's Story of Ravana at the Darbar Festival 2019.

Fig. 3: Mavin Khoo's Story of Ravana at the Darbar Festival, UK 2019. Photo: The Guardian

The progressive development of a diverse, equitable, and inclusive dance education system paved the way for students to engage in the unfamiliar form of Bharatanatyam. Safe environments of teaching and learning that were created allowed students of all ethnicities and beliefs to flourish. The delivery of the module involved negotiations of a range of issues from the smallest gestures and their meanings in the studios, to the larger narratives and embedded philosophies of the art form. These pedagogical strategies extended the reach of Bharatanatyam to a wider demographic in a multiracial country. The nurturing learning spaces allowed for risk-taking, constructive criticism, and robust feedback, and have led to improved teaching and learning methodologies. Indian, Hindu Bharatanatyam artists undertake specific practices, internal processes, reflections, or meditations in preparation for performances. The non-Indian, non-Hindu Bharatanatyam dancers from ASWARA, developed individual pre-performance processes that respected the intentions of Hindu practices, but approached it from personal religious beliefs, blurring the boundaries of race and religion for each of them. The training, engagement, and commitment emerged from a genuine love of the art, which paved the way for personal and professional growth. As artists, they sought universal truths, resonance, and individual interpretations of the practice and texts.

Through their Arangetram and more, these dancers have achieved recognized standards of performance and become advocates for inter-racial and cross-cultural experiences. The barricades of animosity between ethnicities and religions were blurred through the practice of Bharatanatyam. Their bodies and minds became the sites where intersections of race and religion are located and constructed. Rather than allegiance to South Indian heritage, these dancers are writing new narratives of citizenship in a multiethnic nation celebrating diverse cultures and beliefs. Their performativity of the alternative, progressive Malaysian comfortably straddles different worlds on and off stage. Ultimately, if the achievements of these artists can inspire a new generation of Malaysians, perhaps there is hope for a brighter future.

Comments

Post a Comment