Teaching Dance Online: The Turning Point?

Hong Kong experienced great turbulence from June 2019. First, when protests that began as peaceful rallies erupted into violent clashes with the authorities and subsequently caused massive disruptions and followed in February, by the Covid-19 virus that infected the entire world. The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA) is located 200 meters from the Legislative Council in the heart of Hong Kong island and was thus, greatly affected. While this essay draws from the Hong Kong experience, the discussions are relevant for tertiary dance programs across the globe.

2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. (2023, July 14). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019%E2%80%932020_Hong_Kong_protests

One immediate option at tertiary institutions was for deferment of studies. However, this would have an impact on graduating students, preventing some from assuming professional contracts which are scarce even in the best of times. Thus, this was not the preferred option. Dance is a practice-based learning program and the body like any engine that lies idle, will go to waste. Students needed to be supported both academically and emotionally during this time. HKAPA and other leading global institutions immediately moved teaching to synchronous and asynchronous environments such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams in response to these dilemmas. To do this effectively and to ensure the quality of learning for students, teachers needed to make informed choices and decisions for online delivery.

The nature of dance courses in tertiary institutions can be divided into movement-based courses and academic courses. The movement-based and creation courses incorporate learning activities such as technique classes, solo and ensemble practice, rehearsals as well as movement research and choreographic exploration including the use of digital media and technology. The academic courses provide contextual knowledge to conduct research, make presentations, write proposals, safe dance practice, pedagogy and are often delivered via conventional lectures with components of practice.

When much of dance

practice is about time, space and energy, how would teachers adapt the delivery

of classes in confined spaces and across cyberspace? What content could

possibly be delivered and how? This pandemic has also made it glaringly obvious

that despite global connectivity, there are many who struggle with internet

accessibility. Thus, what are the issues of parity and equity that arise and

how are these dealt with?

Friesen (2009) states that “blended learning designates the range of possibilities presented by combining Internet and digital media with established classroom forms that require the physical co‐presence of teacher and students.” The teaching and learning support team at HKAPA designed a blended learning professional development course to explore this mode with the teachers through experiential learning. It consisted of a series of connected face-to-face sessions, supplemented with online activities, independent studies and supported with personal mentoring spanning across eight weeks. The focus of this active blended professional development is to design relevant and connected activities which encourage teachers to apply experience, then reflect and evaluate into their own teaching practice whilst in a learning community. In addition, the range of activities made use of CANVAS,[1] the institution’s Learning Management Systems (LMS) to help teachers understand how different functions and tools could be designed for various purposes. This allowed teachers an opportunity to contextualize its use for their own courses.

For the

practice-based courses, this essay draws from the experience of School of Dance

HKAPA faculty - Malgorzata Dzierzon who is current artist-in-residence, Irene

Lo, part-time lecturer and postgraduate student, and Jake Ngo, lecturer in

Dance Science. Ngo concentrated on body conditioning and strengthening

exercises while Lo on Yoga as well as ballet. Dzierzon was tasked to create a

new work and deliver ballet technique classes. These lecturers dealt with some

preliminary technical issues of sound and clarity but with prompt IT support,

were able to adjust the placement of the microphones and cameras to capture and

record the classes with greater efficiency. Both Ngo and Lo adapted the course

content onto the online platform with relative ease as neither of these

techniques required much use of space. Core competencies through the floor

barre, centre practice with basic, non-locomotor exercises including stretching

and strengthening were achievable. Dzierzon began by sharing her initial

choreographic ideas and research. She instructed the students to develop their

personal responses to the tasks. This was complemented by prerecorded videos, background

reading and viewing material, her individual movement research, presentations

on her work with New Movement Collective,[2]

listening to podcasts and links on CANVAS. This was extensive and required

commitment from students. She also tasked them to work with home-made props or

whatever was available and proceeded to engage them in discussions.

Course designs were based on the VAK model of learning “in order to better process new information or learn a new skill, one must hear it, see it or try it” (Arshavskiy, 2013). Most students respond to a combination of these three approaches depending on the nature of the course. Generally, teachers want to do the same amount of work over the internet as they do in real-time, live teaching. However, academic lessons should be rewritten and divided into bite-sized nuggets of information. This follows the principle of the memory capacity of human beings “seven, plus or minus two” that to ensure better retention, it is best to break lessons up so that they contain fewer pieces of information (Miller, 1956). Weekly quizzes are also a good practice of ensuring memory retention. Arshavskiy (2013) states that “quizzes give learners a chance to apply their knowledge and recall information from the lesson.” Further, this task allows students time to engage at their own pace.

Discussions

Among the most fundamental challenges of online teaching is internet connectivity. Even in progressive first-world cities, there are areas where network coverage is poor. Although Veveona Mosibin, a student at University Malaysia Sabah in Malaysia gained attention for camping overnight on a tree to complete her assignments, students cannot be expected to do that or even sit at a café for hours to attend classes! Keeping cameras and microphones activated for hours each day becomes a financial strain aside from causing online fatigue. In mitigating these circumstances, HKAPA is among a few universities that offered deserving students a subsidy for internet data plans, while most made allowances for student engagement. Teachers were fluid with deadlines while ensuring as far as possible that standards were maintained, and course learning outcomes were fulfilled. The course content information was stored in the LMS to be retrieved at the convenience of the students.

Equity, parity and privacy matters must be a part of the equation. Teachers need to ensure a level playing field and that those from privileged backgrounds are not advantaged because of greater access to technology which includes advanced gadgets, high speed internet, private learning spaces at home and other support systems. Institutions and teachers also cannot expect that all students would be willing to have cameras intrude into their homes and private spaces. Although Zoom does provide for virtual backgrounds, the images do get distorted if you move back and forth. To circumvent this, teachers could allow students to switch off the cameras, which creates another problem of black, empty squares and reduced response or engagement. Students need to be assured that there are going to be no judgements, and learning spaces are safe spaces. They could indicate at the start of the class that there may be interruptions. Re-enforcement and validation of students is a fundamental component of teaching psychology thus nurturing a healthy environment for learning.

Conclusions

2020 has made it clear that tertiary dance programs need to embed online modules into their curriculum from the outset and not as an afterthought. Moving forward, every new faculty should be given training during their orientation on course design incorporating online teaching and learning. Aside from becoming adept with additional modes of communication, technical skills and online etiquette, students must take ownership of their learning. Students should be encouraged to become responsible and autonomous learners which are vital lifelong skills especially for careers that are at best, precarious. They need to be guided towards developing a personal practice and daily rigor that can sustain them in all times.

Dance is a deeply personal, visceral and embodied teaching and learning experience. E-Learning does not and cannot replace the face-to-face processes, but it can enhance the experience. This requires a paradigm shift in preparing for the future. It does open the mind to how and where the arts, dance, teaching and learning can take place.

References:

Arshavskiy, M. (2017). Instructional

design for elearning: Essential guide for designing successful elearning

courses. Place of publication not identified: Your eLearning World.

Baran, E., & Correia, A.-P. (2014).

A professional development framework for online teaching. TechTrends: Linking

Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 58(5), 95–101.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-014-0791-0

Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in a

Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning (2015th ed.). Tony

Bates Associates Ltd.

Beetham, H., & Sharpe, R. (2007).

Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: Designing and delivering e-learning.

Routledge.

Bonk, C.J. & Graham, C.R. (2006). The

handbook of blended learning environments: Global perspectives, local designs.

San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass/Pfeiffer. p. 5.

Cooper, T., & Scriven, R. (2016).

Communities of inquiry in curriculum approach to online learning: Strengths and

limitations in context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology.

https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3026

Czerniewicz, L., Trotter, H. & Haupt, G.

Online teaching in response to student protests and campus shutdowns:

academics’ perspectives. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 16, 43 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0170-1

https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-019-0170-1

Evans, J. C., Yip, H., Chan, K.,

Armatas, C., & Tse, A. (2020). Blended learning in higher education:

Professional development in a Hong Kong university. Higher Education Research

& Development, 39(4), 643–656.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685943

Friesen, N. (2009). Re-thinking e-learning

research: Foundations, methods, and practices. New York: Peter Lang.

Garrison, D. R., & Vaughan, D. N.

(2008). Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and

Guidelines 1st (1 edition). Jossey-Bass.

Jones, E., & Ryan, M. E. (2014).

The Dancer as Reflective Practitioner. In M. E. Ryan (Ed.), Teaching Reflective

Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Approach Using Pedagogic Patterns

(2015 edition, p. 51). Springer.

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M.,

& Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments:

Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. AU Press.

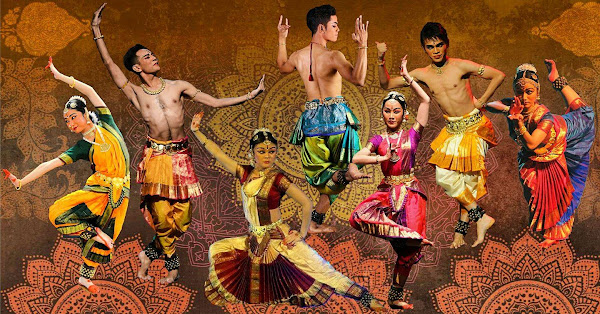

Photos: Irene Lo, Malgozata Dzierzon.

[1] https://www.instructure.com/canvas/en-au

[2] http://www.newmovement.org.uk/

[3] https://www.panopto.com/education-video-platform/?utm_source=ppc&utm_medium=adwords&utm_content=lecturecapture&utm_campaign=lecturecapture&gclid=Cj0KCQjwl4v4BRDaARIsAFjATPkD2hi7D_00TPN-1nTjsAXqu_9ko7mbLi0G9_QggVcGmbueyfq_AtgaAuGpEALw_wcB

Comments

Post a Comment