Singapore Swings and Sways

The Singapore Youth Festival (SYF), launched on 18 July 1967, was originally organized by Education Programmes Division to encourage school-going Singapore youth to develop their artistic talents. Held each year in March and April, the festival gained added significance in 1994, when then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong declared it a national event. Since 2012, its facilitation, and management have been led by the Student Development Curriculum Division of the Ministry of Education.

Despite its national endorsement, the

organization of the festival has not been smooth sailing. It has encountered challenges and

resistance from a society driven by academic excellence and financial success,

particularly in the 1970s, as a developing nation. The primary reason was many felt that

devoting numerous hours to rehearsals and performances would keep the students

away from their textbooks therefore affecting their grades, and jeopardizing

entrance into prestigious universities. The initial mindset was that there was

little to be gained from the arts. However, with concerted efforts from those

who passionately believed in the benefits of artistic pursuits, supported by

scientific research into the value of modes of learning, multiple

intelligences, right brain-left brain studies, childhood development,

recognition given to extra-curricular participation, the festival came back

bigger and stronger.

Today for a small nation with a population of approximately 5.5 million which is the jewel in Asia’s economic landscape, the annual participation of more than 40,000 young children who sing, dance, act, and or play musical instruments is an important and impressive statistic. Add this to the numbers who support from the periphery or are directly involved - parents, teachers, instructors, costume designers, make-up artists, back-stage and technical crew, it is heart-warming for arts practitioners and lovers that this has become one of the focal points of Singaporean life, at least for one season in a year.

The SYF is a tremendous grassroots arts program and specifically for the purposes of this discussion, dance, that is incredibly effective in introducing children to the joy of dance and simultaneously inculcating values of teamwork, cooperation, leadership, good ethics, and proud nationhood. This is seen as an integral part of the efforts to develop and provide wholesome education for each child growing up in Singapore. Having a different theme each year since 2000, such as Symphonic Canvas for 2012, or Aspirations in 2011, the SYF serves to provide and stimulate the child’s learning process through alternative means beyond the formal classroom.

The dance sections are divided into categories of Chinese, Malay, Indian, and

International dance and into primary and secondary-junior colleges that

participate every alternate year. My involvement began in 2010 with the

invitation from Dr. Peter Gn, the Senior Specialist (Dance) to adjudicate the Malay dance category. While concentrating on this

category, I was fortunate to witness the Choir presentations in 2011, which has

assisted in gaining broader insight into this phenomenon and made involvement a great personal learning experience. Each participating school must present one item of between

4 to 7 minutes with marks deducted if they exceed the stipulated time allotted

which is best practice in all competition-type situations. The reward system implemented was not first, second, or third prizes,

but initially Gold with Honours, Gold, Silver, and Bronze medals, and a certificate

of participation.

In the last few years, the awards have evolved into a

simpler structure of Distinction, Accomplishment, and Commendation. The adjudication

panel comprises practitioners and or scholars such as Cultural Medallion

Awardee Som Said, Zaini Tahir, Artistic Director of the Republic

Polytechnic Cultural Centre, both from Singapore, and regional experts from Indonesia or Malaysia.

The 2023 panel included Norisham Osman and Dr. Mohd Noramin Farid who represent

the younger practitioner-scholar voices of Singapore. There is no mandate from

the organizers about the overall percentage of Distinctions to be awarded and

the judges are constantly reminded to base their results on the merit of each

performance.

Figure1: 2023 Adjudication Panel for Malay Dance with Dance Director for CCS,

Dr. Peter Gn

The intelligent strategy of the Ministry of Education to refer to this event as a festival, is intended to remove the sense of competition between schools, principals, teachers, and choreographers, although this is inevitable. Singapore is known as a country that places great emphasis on achievements, resulting in a highly competitive mindset. Thus, there is an obsession to obtain the highest award, giving the schools bragging rights. It is possible that students, teachers, and choreographers come under tremendous pressure to deliver. However, the objective of the festival is to celebrate the creative expressions of the children and to encourage the love of dance. Despite what might transpire behind the scenes or during the process, from the vantage point of the jury, what shines through in the festival is the unadulterated joy that the children display in their presentations. The attention to detail in the dance routines, movement technique, floor patterns, costumes, and make-up are clear indicators of the commitment and passion of all involved. The performers exude confidence that belies their age, and kudos to them.

In the interest of constructive criticism towards enhancement, there are some issues that may be addressed for the SYF. First, is the categorization of dances for the festival according to ethnicity. This is possibly the simplest and most effective method to separate the groups; having one large group under the dance umbrella would just be too much to handle. However, coming from Malaysia, it is my own albatross of being ultra-paranoid about divisions according to ethnic identity. Another pet grouse of mine is that in a children’s dance competition, children should look like children, and having them excessively dressed and made up is a little frightening and unnecessary if they are presenting a simple folk dance. Every aspect should be age appropriate. The tendency for the choreographers to adorn the child dancers with big wigs, sequined eye-shadow, and lip gloss, with large decorative headwear and ornaments, detracts from the quality of the dancing and attempts to make the young dancers look more mature than necessary. The essential lesson for anyone who deals with children’s dance is to first remember that they are children. Further, it is encouraged that trainers spend as much time as possible on the fundamentals of each dance genre, rather than being focused on the choreography. Besides the movement technique, there ideally should be sufficient time spent on delivering contextual knowledge of the dances too, while making it assessable and enjoyable.

In the meantime, aside from the SYF, other companies and organizations are also making efforts to develop talent, audiences, and choreographic skills. One such annual event that is growing in stature is Sprouts, a national choreographic competition organized by the National Arts Council (NAC) Singapore in cooperation with Frontier Danceland, a non-profit dance company established by Low Mei Yoke and Tan Chong Poh in 1991. The objectives of Sprouts are to identify talent and to provide a platform for the creation of new ideas for dance by aspiring choreographers in all genres of dance techniques. The process involves a pre-selection and two rounds of showcases followed by a Preliminary Round and then the Final Showcase. Both event rounds are performed before a live audience, as well as a jury comprising invited members of the performing arts industry. I was privileged to adjudicate the 2011 edition which was the third in this series, held from 23 July to 3 September. The information about the choreography selected for the finals including synopsis, themes, and creative teams was sent to the adjudicators two weeks prior to the competition. This gave the judges sufficient time to reflect, form impressions, make notes, and develop a visual expectation of the work. This process is challenging since the adjudicators have to make decisions based on the merit of the choreography after watching the dance which lasts approximately 8 minutes. Often, this is too brief to grasp in its entirety however, with an experienced panel of choreographers and producers, and followed by healthy discourse, this is best practice. A note to the choreographers submitting their written proposals, which include digital material of previous choreography, it is crucial to present the best work possible with good quality writing and recording. First impressions count, and choreographers are encouraged to seek the assistance of creative producers for this purpose. Newness of themes, originality, concepts, and movement vocabulary in any choreographic competition, are often listed as the primary criteria for adjudication. However, the reason that Lin Hwai Min, Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Kazuo Ohno, and Pina Bausch are hailed as geniuses is that they are rare. Thus, it is challenging to achieve newness, and its interpretation is very reliant on the experience and exposure of the choreographer, the jury, or the audience Thus, in my years of being committed to dance, while this remains a yardstick and my own personal aspiration as an artist, I generally temper my own expectations.

Figure 2: Sprouts 2015.

10 choreographers were

selected for the final round and prizes were given for the Most Promising Work,

receiving a cash prize of S$2,000, an arts professional Development Grant of

S$3,000 to pursue further training in choreography and the opportunity to

present work the following year, the Best Dancer who receives S$500 cash, and

Most Popular Work wins S$1,000 through audience vote while all finalists

receive S$500 for assistance towards production. Other small scholarships and

opportunities are also given as incentives. The previous year’s winner Liz Fong

was invited to stage her work as part of the prize and to assist in continued

development. While the prize money may appear unsubstantial, it is nevertheless

very useful to the budding artist as a start. Contemporary dance choreographers

are all too familiar with working under dire conditions and constraints of zero

budgets, and while these amounts seem paltry, at least they attempt to provide

seed money to meet minimal production costs. Christina Chan’s Something Shifted emerged as the overall

champion of Sprouts 2011. A

professionally danced duet by Christina herself and Malaysian dancer Lu Wit

Chin, using a jacket as a prop and as costume, she manipulated the attire to

tell the story of the relationship between two people that keeps shifting. A

simple plot that was easily accessed by the jury and the audience, the maturity

of the performance won everyone over. This winning choreography was a case in

point that perhaps the ideal of the competition is to unearth new approaches

but in reality, since the choreographers are generally young, this will take a

long time to nurture. However, in its aspiration to encourage and uncover new

talent in choreography, I believe that Sprouts

is on the right track to achieve its goals. As a testament to the importance of

continued support and the value of the prizes such as short-term study

programs, the invited performance of Liz Fong who created Scale and Sarcous, displayed a greater level of maturity and

ability to present simple themes within a more challenging choreographic

structure.

Both the SYF and Sprouts are examples of programs and structures that have been instituted solely by the government or in collaboration with private companies to enhance the standards and appreciation of dance. The support of corporations has not been discussed in this essay but it is suffice to say that the establishment of the Yong Siew Toh Conservatoire of Music at the National University of Singapore in 2003 serves as a shining example of the pursuit of excellence in performing arts in this tiny nation-state. In 2008, the first pre-tertiary high school that incorporated artistic pursuits alongside the International Baccalaureate, Singapore School of the Arts, with state-of-the-art facilities was established. 2024 will see the first intake of students under the freshly minted University of Arts, Singapore which will house the long-established Lasalle College of the Arts and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts to offer degree programs under its banner. These are just some of the outstanding examples of arts education that should become case studies for Singapore’s neighbors to learn from and emulate.

Regionally, the Singapore International Arts Festival (SIFA) is one of the most established multi-genre events that include exhibitions, performances, and commissions from the most renowned to lesser-known cutting-edge artists. It is now in its 46th year and helmed by Artistic Director Natalie Hennedige, organized by Arts House Lab (AHL) and the NAC. Francis Liew, an independent producer presents a small Asia Arts Festival aimed at bringing together people of all ages practicing all genres. Working with a minimal budget, this festival provides opportunities especially for the young to hone their performance skills. Meanwhile, private studios offering ballet continue to thrive with Singapore Ballet Academy being the oldest in the business opening its doors in 1958, while newer genres of flamenco and street dance, are gaining a foothold through efforts of Antonio Vargas' Flamenco Sin Frontier and street dance programs such as Shift (up to 3 years of professional development for street dancers), Stirring Ground (creation and movement exploration mentorship) and Youth Space Online (mentorship for underprivileged youth) encouraged by the NAC. Other artists such as Kavitha Krishnan and her Maya Dance Theatre work tirelessly to produce cross-cultural projects and works with dancers who are differently abled, while Janek Schergen's Singapore Ballet, Kuik Swee Boon’s T.H.E. Dance Company, Osman Hamid’s Era Dance Theatre, the Bhaskar family’s Bhaskar’s Arts Academy, and Som Said’s Sri Warisan are tirelessly campaigning for dance awareness, excellence, and professionalism within their preferred genres of dance. Examples of projects include Maya Dance Theater’s Release, a potential annual program of new contemporary dance works that try to incorporate young choreographers from foreign countries working alongside local dancer-choreographers, Muara Festival of Malay dance organized by Era Dance Theatre or Sri Warisan’s Malay musical theatre production of Bendahara and the Bhaskar’s Bhaskareeyam Festival for Indian arts. Grassroots programs are critical for the development of any field of specialization.

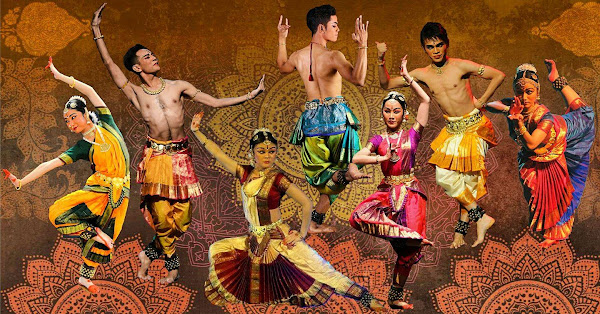

Figure 3: Bhaskareeyam 2022

Figure 4: Muara Festival Presentation; Photo: Heinkel Heinz

The above examples attest to the vibrant ecosystem of dance that

is serving Singapore well, not only in molding dance professionals for the

future but in building audiences that will support the industry through

participation, and patronage.

ENJOYED READING

ReplyDeleteThank you so much!

Delete