Moving Bodies, Navigating Conflict: Practicing Bharata Natyam in Colombo, Sri Lanka by Ahalya Satkunaratnam - a book review

The book Moving Bodies, Navigating Conflict: Practicing Bharata Natyam in Colombo, Sri Lanka published by Wesleyan University Press in 2020 details the complex location and representation of Bharata Natyam, a classical dance form accepted to have emerged from the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The author, Ahalya Satkunaratnam is a professor of arts and humanities at Quest University Canada and a Bharata Natyam exponent with a diverse, multinational upbringing that is reflected in her approach to research and academia. Added to the lens of the postcolonial feminist scholar, this study on the practice of Bharata Natyam in Colombo, Sri Lanka is ground-breaking. She has researched and described in the most poetic, academic language, the intricacies that can be read into the practice of Bharata Natyam. What has made it even more fascinating, is that this foregrounds the civil war of Sri Lanka and the heightened religious and ethnic wars that have plagued the country. Satkunaratnam elucidates and untangles the web of considerations and negotiations in practicing Bharata Natyam as well as what it represents in Sri Lanka. Written in four chapters Meaning Making, Public Aesthetics, Public Education, Staging War, and Shakthi Superstar, together with an introduction and a conclusion, it carries the reader through the maze that is Bharata Natyam practice in Sri Lanka in a gentle, carefully thought-through and designed research and outcome. It helps even the most unexposed reader understand these complexities.

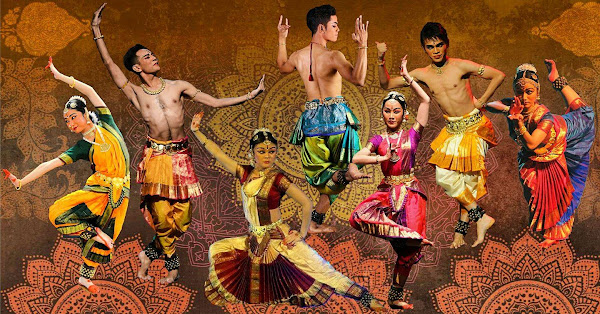

The book's theme is set quickly in the introduction Maneuvering Identity, Shifting Nations most eloquently. The opening description of the group of Bharata Natyam dancers sets the tone with the sudden shift from the Carnatic song to the popular melody of Gajaga Vannam. The book begins with questions of the practice of Bharata Natyam in a militarized nation, shattered with conflict of ethnic wars, and how different dances represent warring factions of the community. It is both fascinating and horrific simultaneously. The detailed explanation of ethnic divisions, language, religion, and culture provides the background against which the reader can understand and visualize this phenomenon.

Chapter One begins with a short,

descriptive paragraph that leads to a reflection of studying Bharata Natyam by

one of the main respondents Daya Mahinda, Satkunaratnam then begins to weave

the explanation of the dance form as a cultural marker for the Tamils of Sri

Lanka, and how it was transported from its original space of Tamil Nadu. She

couches her work in the academic writing of Homi Bhabha, providing a strong theoretical

framework for her research. Delving deeply into the concepts of

transnationalism and translational, she claims “Bharata Natyam is the cultural

sign in translation” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 21). These

ideas are further consolidated with the theories of Butler. What this even more

profound is the research locates the practice of Bharata Natyam against the

civil war of the nation, and this would be difficult for the reader to imagine

if not so eruditely written. The discussion about the prevalent class system, of

caste and social status, and the tensions for a female child drawn to the dance

form “the ideal Tamil woman was an ideal wife and mother, and dance did not fit

within those criteria” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 24). Social reform was taking place

in this period, as well as the national identification of Sri Lanka with

Buddhism, and the Sinhala language. The role of the women’s organization was important

in the resurrection and sanitization of traditional dance as the opposition to

years of colonial mastery and dominance. The chapter includes a robust

discourse on the role of Kalakshetra and its transformation from the dance of the

temples to that which is accepted within the upper castes of society. This is

of paramount importance for the readers to take away, that Bharata Natyam indeed

was reconstructed with a particular agenda. The importance and the evolution of

the All-Ceylon Dance Festival is significant in the shifting position of

Bharata Natyam and is well recorded in this chapter followed by the explanation

and description of the crises after the Black July event in 1983.

The

insightful chapter Public Aesthetics, Public Education follows with an

in-depth look at public education in Sri Lanka. This was an eye-opener since as

early as 1972, Sri Lanka became the first country to include the study of

aesthetics into the national education curriculum on par with language, Math

and Science. This was phenomenally progressive. The role of the government in

promoting the idea of the postcolonial mindset through the arts and aesthetics

of visual arts, dance, and music rooted in the local was a sign of their forward

thinking. The author sees this as a “type of development project for the

postcolonial nation, weaving cultural nationalism with neo-liberal

developments” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 53) while obtaining foreign aid is a common

feature within the Asian nations. There is included a debate about language, as

well as the privilege of the English education sector. Again, this is a similar

pattern seen in numerous nations colonized by the West. One of the most

important points that the author makes here is that it is “the female body that

is the repository for the interweaving, communal, and national identity” (Satkunaratnam

2020, 54) and its primary site, as the students and teachers of Bharata Natyam.

She takes us through four case studies with distinct experiences and highlights

some challenges and contestations they face. For example, the

examinations at O- and A-Levels for Bharata Natyam are available only in Tamil

while those of Kandyan dance are only in Sinhala. The limitations of the

curriculum are glaringly obvious where the dance steps learned are too

rudimentary, and students who are interested in these art forms see it only as

a means to review what they already know. This is far from the ideals of

education. Creativity too, is difficult to be taught and assessed as it

requires too much standardization, memory, and theorization. Nevertheless, for

the artists employed within this system, it provides financial stability that

is not easy to be had within the arts.

Chapter Three begins in a familiar writing style of description of a scene that sets the tone of what will be discussed, namely strategies of choreography during the war. The researcher is driven by two research questions that she addresses in this chapter which are connected to the choreography that situates itself within conflict zones, and how “the bodies as producers of movement and markers of ethnicity” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 78) impact the works. This contemporary approach to understanding dance as relevant in our times is vital for the continuation of a dance form. The two case study choreographies are Draupadi Sabatham by Chandran, who was asked to present a piece on war, and selected this excerpt from the Mahabharata epic to do so, and her other work, Shakti. The researcher records the inspiration, and the thought processes of a Tamil woman to use Bharata Natyam to navigate and negotiate ethnicity, geography, and a political crisis. The researcher herself was reflexive in her analysis and personal response to war and wondered if her own emotions were heightened when compared to those who were literally living through it. This chapter will particularly resonate with choreographers who are working in areas of conflict and undergoing similar challenges, making compromises, or choosing which battles to fight themselves. This calls to mind the work of Rose Martin, whose book Sustaining Dance in Turbulent Times: displacement, identity, and the Syrian Civil War where she notes that the element of war as a backdrop for making or working in the arts, could often be overlooked. The author parallels the character of Draupadi whose “body was the prize for the highest wager in the game between family members” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 89), stating that in war, sexual violence against women is a cruel device.

In

Chapter Four, the author-researcher looks to further the analysis of

choreography and draws from the experience of performing in the nationally

televised dance show Shakti Superstar, a Tamil language, Sri Lankan

program like American Idol. As with popular entertainment the world

over, the author describes the need to combine the traditional dance of Bharata

Natyam with commercially assessable Bollywood dances. She notes that “the

confluence of global forms like Bollywood and Kollywood with Bharata Natyam and

Kandyan dance produces a uniquely local experience” (Satkunaratnam 2020, 109). As

a participant in the work Title Dance, the researcher provides a cogent insider

perspective to all the negotiations that were taking place – from the challenge

of selection of dancers to the music and the vocabulary. Most importantly too,

what this choreography would represent, inscribed on the female dancing bodies.

This valid reflection and analysis are useful to the practitioner who straddles

these two worlds quite often out of necessity and sustainability.

In

conclusion, this book is an excellent example of rigorous fieldwork, extensive

literature reviews, academic theories as well as embodied research practices

written by an author with tremendous command of the English language. It is

highly recommended for practitioners of Bharata Natyam, and beyond. Any

researcher and practitioner working in areas of conflict and working with art

forms that have a wide diasporic practice will find this a must-have in their

libraries. The language of the book and its contents would be particularly

resonant with artists and choreographers working within Asian dance forms, or

in countries that have been colonized, and all the negotiations that come with

keeping the practice alive.

Comments

Post a Comment